Beginning in 1961, the American Heart Association (AHA) began recommending Americans reduce saturated fat intake. By 1973 the AHA went a step further in recommending Americans limit saturated fat intake to <10% of total daily calories. This advice was based upon the recognition that saturated fat consumption and its ability to increase blood cholesterol was strongly correlated to the incidence of heart disease. As such, it was (and still is) recommended that saturated fats, especially from animal sources such as red meat, eggs, and cheese be limited.

In recent years, the scientific community has challenged the saturated fat/heart disease hypothesis and reignited the debate regarding the relationship linking saturated fat to the development of heart disease. At the same time the popularity of the Paleolithic (Paleo) diet has exploded within the fitness community. The Paleo diet is based upon the foods that were consumed during the Paleolithic era, which spanned the vast majority of human history, starting ~2.4 million years ago and ending ~10,000 years ago. It was around this same time that many of the mobile hunter/gatherer societies were slowly transitioning into stationary farmers.

The hunter-gatherer philosophy of the modern day Paleo diet includes many of the foods that were available to the Paleolithic man including fish, eggs, meat, nuts, seeds, vegetables, and fruit and excluding those that were not, such as highly processed foods, dairy, grains, and legumes.

In comparison to modern day dietary guidelines, the Paleo diet does an excellent job of emphasizing fish, nuts, seeds, fruits, and vegetables while also excluding highly processed, high carbohydrate foods. However, the Paleo diet’s emphasis on high protein consumption, which in today’s modern societies likely comes from meat consumption (and not just fish and chicken) is in direct conflict with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans and the AHA recommendations due to the diet’s concomitant high intake of saturated fat.

Now to be fair, there is some recent evidence in modern humans, anthropological evidence in our Paleolithic ancestors, and more recently in the Inuit population of Greenland that a diet high in saturated fat and animal protein caused little to no heart disease; however, in recent years the absence of heart disease in populations eating a diet high in saturated fat has also largely been debunked.

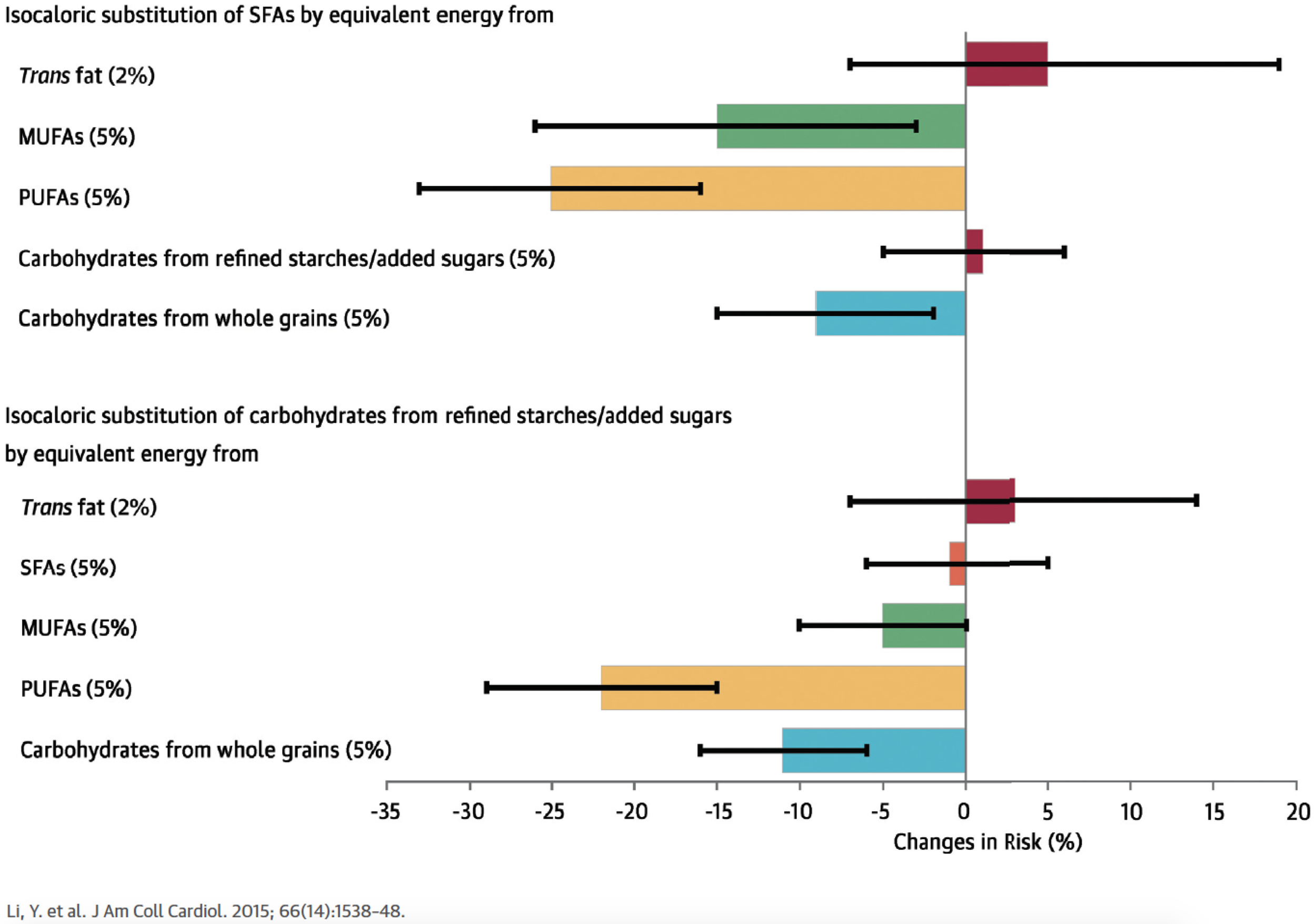

Figure 2. Type of Dietary Fat and Risk of Coronary Heart Disease. E = % isocaloric change in energy intake in place of carbohydrate. 1%E = 1% of daily energy replacement of carbohydrate with fat, 2%E = 2% replacement of carbohydrate with fat, etc. Trans = trans fat; Sat = saturated fat; Mono = monounsaturated fat; Poly = polyunsaturated fat.

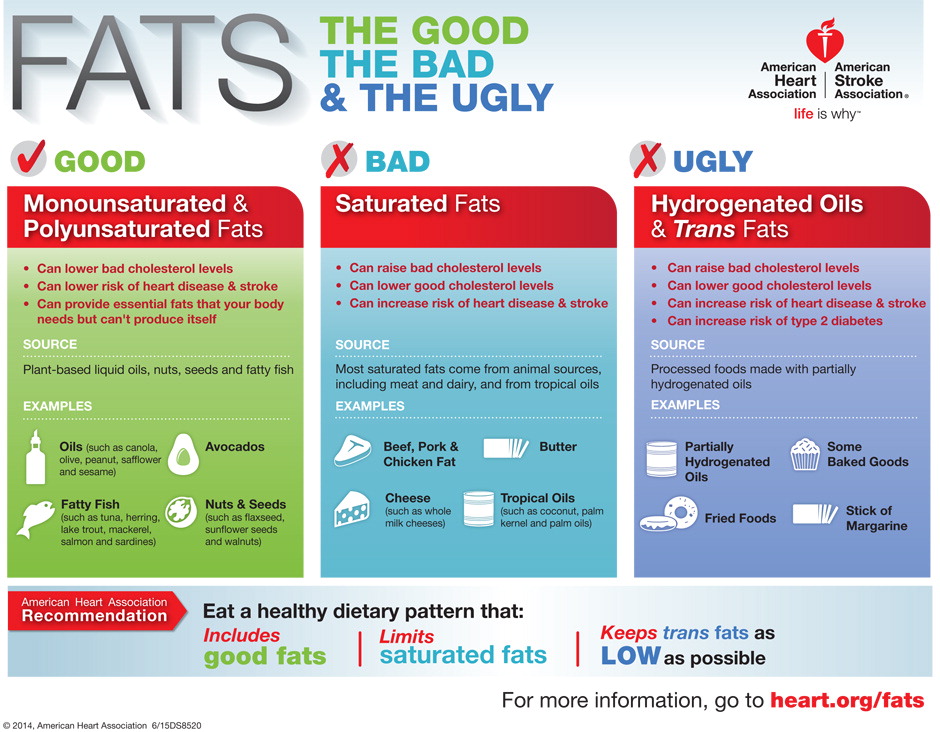

The best available evidence we have on the relationship between dietary fat and heart disease suggests that trans fat (partially hydrogenated fats that are solid at room temperature and found in cookies, cakes, and pastries as well as other highly processed goods) are by far the worst types of fats, followed by saturated fats, monounsaturated fats, and polyunsaturated fats.

Figure 3. Fats, Carbohydrates, and Heart Disease: isocalorically substituting fat for carbohydrates on the risk of coronary artery disease. Substituting saturated fat (SFAs) with refined carbohydrates does not change your risk. Substituting SFAs with MUFAs (monounsaturated), PUFAS (polyunsaturated) or whole grains decreases your risk of coronary artery disease. Trans fat always increases your risk.

The vast majority of modern day Paleo diets rely heavily on coconut, butter, ghee, avocados, and olive oil. In and of itself, the use of cooking oil in the Paleo diet is interesting as the development and use of cooking oil occurred after the Paleolithic era ended (for example: the earliest accounts for the use of olive oil occurred within the past 6,000 years, well past the end of the Paleolithic era of 10,000 years ago). Furthermore, the Paleo diet relies upon the use of butter and ghee, which are both dairy products and thus should technically not be part of the Paleo portfolio.

This article is not meant to be an indictment against the Paleo diet but the Paleo diet does help to put the use of coconut oil into a context many of us are familiar with. For many Paleo enthusiasts, coconut oil represents the exclusive cooking oil. Butter is linked to the development of heart disease but butter is an animal-based, saturated fat product. On the other hand, coconut oil is a saturated fat but is a plant-based product. So, are people who ingest lots of saturated fats through coconut oil home free from worrying about heart disease?

Butter is an animal product and coconut oil is plant based. With that in mind, is coconut oil bad for us, good for us, or none of the above?

The proponents of coconut oil will argue that the difference between butter and coconut oil lies in the fact that coconut oil, although largely composed of saturated fat, contains a different subtype of saturated fat. Coconut oil’s type of saturated fat is a medium chain triglyceride, whereas the saturated fat in butter is a long chain triglyceride. Without getting too technical, medium chain triglycerides are metabolized by the liver directly into energy and do not participate in the synthesis of cholesterol, whereas butter does.

However, with all that being said, when we recently spoke with a leading expert (whose name wished to not be disclosed) on the relationship between heart disease and diet in the field of medicine regarding the potential health implications of the use of coconut oil in every day cooking. She told us that

“... as you know it's only within the last 5-7 years that it's (coconut oil) become a popular oil in (certain groups) of the US population, although it's certainly been a common oil in Asian, African, and some South American populations for decades, if not millennia.

A PubMed search for "coconut oil" predominantly results in animal studies, reviews, and a few small trials - predominantly in Asian populations - thus very few (well, I haven't seen any) long-term large-scale human observational studies or trials specific to CVD precursors, and none of "hard" CVD endpoints. The few short-term trials in humans occasionally show differences, and occasionally show no differences in cholesterol and/or lipoprotein levels compared with a variety of other fats/oils, depending on the study race/ethnicity, underlying medical conditions, duration of feeding, sample size, comparison oil(s), etc.

So, there are a few human studies on inflammatory and lipid markers, a few on unrelated outcomes (skin conditions/diseases, predominantly), but in my opinion, nothing definitive one way or another with respect to CVD. In other words, if you compare the coconut oil literature to the evidence base that exists for olive oil in CVD, it's like comparing an ant hill to the Alps. And, importantly, it took that mountain of evidence on olive oil before it could start being consistently recommended by major organization/government guidelines as cardioprotective. In other words, there's still a long way to go before we can declare coconut oil as benign, helpful, or harmful for CVD or other cardiometabolic conditions.”

In summary: It’s still too early to tell if coconut oil is “bad for you, good for you, or none of the above”. So before you start exclusively using coconut oil as your primary cooking oil source, let other people be the epidemiological guinea pigs and use olive oil or another mono- or polyunsaturated fat as your primary cooking oil source. The worst type of fat you can eat is clearly trans fat (avoid by looking for partially hydrogenated on nutrition labels) so stay away from that. The jury is still out on coconut oil.

So Why Even Use Coconut Oil? Coconut oil is tremendously delicious when used in the kitchen, as its full, rich fatty flavor is enhanced when virgin un-refined oil is used, providing a deep coconut flavor. It is perfect for adding moisture, and a rich-mouth feel to baked goods of all varieties, without adding an overpowering flavor of only coconut. It is also perfect for stir-fry, roasting vegetables or mixing it into a morning oatmeal. There are many great recipes that provide a variety of ways to cook with coconut oil.

Coconut oil is solid at room temperature, as other saturated fats are, but its melting qualities are superior for various cooking purposes. If you wish to use coconut oil to cook with, do so sparingly, mixing your oil choice with other options such as olive oil, canola oil, and peanut oil to incorporate other fat sources. Be sure to mix it up: remember, a healthy diet consists of BALANCE, so mixing up your oil choices is a large component and helpful hint in practicing this.

Best,

MacKenzie Spears

Todd M. Weber PhD, MS, RD