Eating healthy doesn’t happen overnight, it’s a life-long process of trial and error. For anyone who tells you otherwise, they're wrong. You’re not going to fix your diet in one fell swoop. It takes time. It takes energy. It takes effort. But you know what, it’s totally worth it. Once you’ve got your dietary system in place, eating healthy becomes so much easier. I wouldn’t go so far as to say that it is effortless but it is much easier. I like to tell people that if they put in the work now and establish a good foundation that later on they won’t have to focus so much time and energy on eating healthy. This allows them to focus on the more important things in life: friends, family, experiences, and good times.

The long and winding road of healthy eating.

To illustrate what I’m talking about I’d like to share my healthy eating journey with you. I still don’t eat as well as I should, but I’ve come a long, long ways. I’ve built my foundation and now I don’t have to spend as much time, energy, and effort in eating healthy.

Despite becoming a registered dietitian my dietary habits didn’t really change from high school through my Master’s degree at Iowa State. My diet consisted primarily of peanut butter and jelly or lunch meat sandwiches, cereal, black bean salsa, and frozen pizzas along with “healthy” snacks such as string cheese, yogurt, carrots, and nuts. My diet during this time wasn’t necessarily unhealthy, it was just extremely limited.

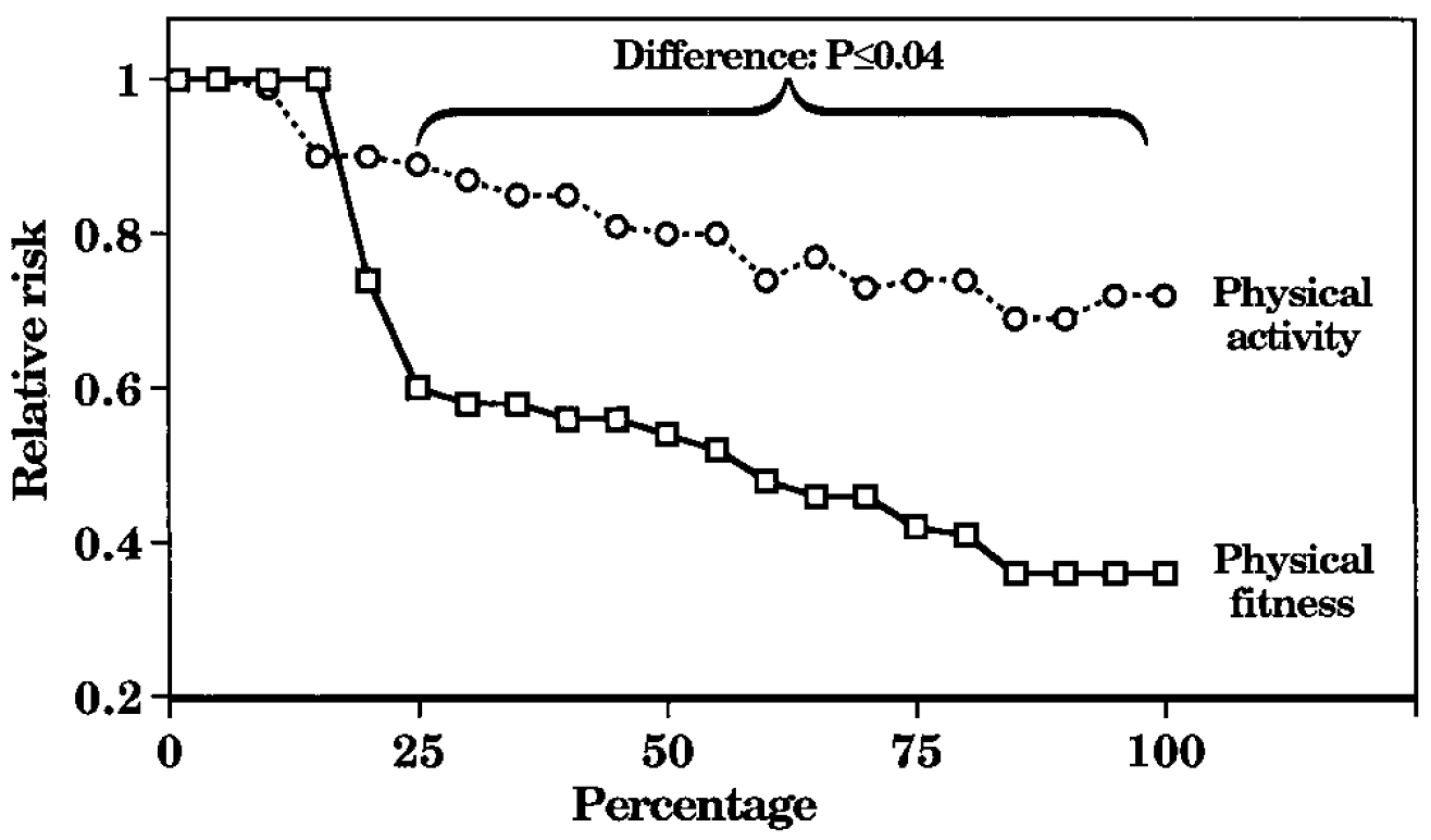

From high school to the beginning of my time at East Carolina University (ECU) I was extremely physically active, which helped me get away with poor dietary practices. The first semester at ECU I stopped riding my road bike (as a result of a chronic back injury), ate the same diet I was accustomed to eating as an athlete, studied all day, drank too much alcohol, and gained 20 pounds….my freshman 15 came during the “freshman” year of my PhD.

After my first semester at ECU I transformed myself back into the weight lifter I was during my undergraduate days. I hadn’t seriously lifted weights since college but with my back not cooperating and no longer having hours and hours to ride my road bike anyways, the transition to weight training was a necessity. During this time, I also had to “unlearn” all the poor dietary habits that I had previously undertaken as a road cyclist to maintain my body weight. The high sugar yogurt, eating bagels instead of bread, and other high calorie dietary habits that I had previously adopted to maintain my weight needed to be changed.

One of the advantages I had at ECU was that we were connected to a medical school with a hospital cafeteria. This provided me with an entrée and two vegetables every day for lunch. It was during this time that I also finally started making tacos and a few other meals at home on my own. During my last year at ECU my girlfriend (now wife), Kathleen and I moved in together. She cooked far more than I did and I picked up a few of her recipes. I probably only really knew how to cook around 10 meals at the time but it was a start.

In January of 2013 I moved to Denver, CO with Kathleen. In Denver, Kathleen and I slowly started cooking more and more meals. To be honest, part of this was for health reasons but the major reason we started cooking more was to save money. Between my unsteady job prospects and my wife’s post-doctoral fellowship salary, we didn’t have a lot of money to eat out. We slowly and progressively added more and more meals to our repertoire. I don’t have exact numbers on how many meals we added each year we’ve lived in Denver but today we have 103 recipes in our recipe manager (Paprika). To be fair, I recently went through our recipe manager and deleted out 50 or so recipes that we either a) downloaded from the internet and never made b) made the recipe but didn’t like it or c) decided it was far too much work to make again.

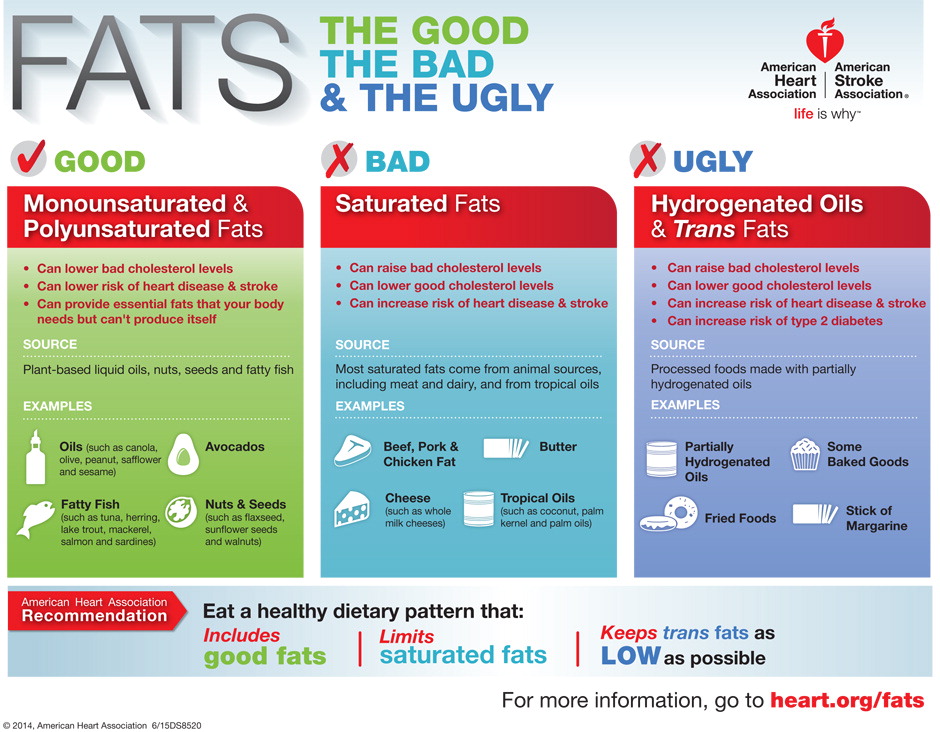

During our time in Denver we’ve also branched out and learned how to make several vegetarian based dishes such as quinoa, couscous, quiche, and a variety of bean-based dishes that are now staples of our diets. We have ditched regular yogurt for Greek yogurt, tried to eat more nuts, and eat quite a few hard-boiled eggs.

Our newest meal-planning endeavor is to plan our meals for an entire month at a time. This will prevent us from needing to plan meals out each week prior to grocery shopping. Neither one of us enjoy this task, so only having to complete it once per month or once every 2 months is a welcome change. To help with our monthly planning we have also developed the following weekly system to guide our recipe selection and grocery shopping:

1) Breakfast:

- Individualized options, Kathleen and I tend to have different preferences for weekday breakfast (i.e., bagel with cream cheese/peanut butter, oatmeal or smoothie)

- One weekend morning brunch meal (e.g., eggs, potatoes, breakfast burritos)

2) Lunch: vegetarian based recipe

- Usually a single main dish supplemented with snacks (e.g., fruit, yogurt, string cheese, nuts, cut up veggies, and granola bars)

- Vegetarian emphasis: 8 out of 10 of our current lunch specific meal recipes are vegetarian

3) Dinner:

- Pre-plan 4 meals/week

- At least 2-3 of these meals have to make enough to have leftovers, which supplement the other 3 dinner meals of the week

- We have ~40 consistent recipe options that we choose from with the goal of trying at least 2 new recipes per month

- Of the 4 dinner meals we are making a concerted effort to eat at least one vegetarian meal, one fish-based meal and the other two can be meat based

- We use our crockpot at least once, if not twice, per week

- We usually cook at least 1 of our 4 pre-planned meals on Saturday/Sunday to allow for recipes that are more complex or have longer cooking times can’t be done during the week

We’ve come a long, long way since my college days of peanut butter and jelly sandwiches but these changes didn’t just happen overnight, they took over 5 years and are still a work in progress. In the process of making all of these dietary changes we have:

- tried ~50 recipes that just didn’t stick

- still don’t have great fish recipes

- need to find more good vegetarian dishes

- have tried Blue Apron and didn’t really like it (If you want to know why it didn’t work for us, let me know and I’d be happy to share my thoughts. Our dislike wasn’t with Blue Apron specifically, it’s just the brand we happened to try)

- struggled with finding time to grocery shop and prepare meals

- ignored planning weekend lunches (we need to tackle this next!)

But you know what? We’re pretty happy with where our diets are today and someday soon we’re going to (finally) get to a place where we have our routine down. We like the foods we eat and the rest of our lives have become so much easier (or unburdened) by being able to eat healthy, remain healthy and active, lean, and when we do go out or want to have some cookies or ice cream, we can easily fit them into our diets without feeling one bit of guilt. We have never sacrificed taste for health.

Instead of trying to make several grandiose changes that you and I both know aren’t going to stick, make a commitment to sustainable, lifelong changes. Start to change the small things in your diet that can make you healthier today. Realize that to be successful, you will need to commit to it for the long term. In the end, you’ll be so much happier that you did.

Not everyone has to follow our template, the way we do things is only a suggestion and is still evolving. However, we have developed a system that works for us. In 2018, I hope that you take a little time, energy, and effort to develop or refine a system that works for you. In 2019 and beyond, you’ll be glad you did!

Todd M. Weber PhD, RD